October 23, 2024, Bacteriophage

Foreword

Why Are Bacteriophages Making a Comeback?

Bacteriophages, as we know, are viruses that use bacteria as their hosts and are widespread in nature. We can apply bacteriophages to clinical treatment by leveraging certain characteristics: they exhibit strong specificity in combating bacteria, do not disrupt normal flora, and do not infect eukaryotic cells; they rapidly infect and lyse bacteria while possessing the ability to self-replicate. The resurgence of bacteriophages in combating bacteria after over a century can be attributed to the widespread prevalence of superbugs in our environment. We conduct bacteriophage clinical trials to investigate the mechanisms of action related to bacteriophages, hoping they will emerge as a novel antibacterial therapy. In the realm of antimicrobial therapy, bacteriophages diverge from the traditional path of antibiotics. Antibiotics are characterized by broad-spectrum activity, multiple selectivity options, and strong compatibility, though these attributes apply primarily to common bacteria. With decades of research and production history, we possess a thorough understanding of the research background and mechanisms of antibiotics, making their clinical application straightforward. However, the prolonged misuse of antibiotics has fostered drug resistance through various mechanisms, such as the production of β-lactamases, enzyme inactivation, biofilm formation, bacterial cell wall thickening, drug entry channel blockage, and efflux via cell membrane pumps, among others. When a bacterium acquires these functions, it may become a “superbug.” Bacteriophages are the natural predators of these target bacteria. They can degrade biofilms, promote bacterial clearance and tissue repair; their self-replicative nature eliminates the need for prolonged administration, giving bacteriophage therapy clear advantages.

Characteristics of Superbugs in Genitourinary Tract Infections

There are several clinical classifications of urinary tract infections (UTIs): 1) Upper UTI, lower UTI, and total UTI based on the site of infection; 2) simple UTI and complex UTI based on the presence or absence of a specific underlying cause. The primary causes of complex urinary tract infections include urinary obstruction, urinary system malformations or dysfunction, long-term indwelling urinary catheters, device-related procedures, tumors, and histories of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, among others. 3) Based on the classification of secondary infection correlations: A, after treatment, symptoms resolve, urine cultures are negative, but symptoms reappear within 6 weeks. B, urinary bacterial counts ≥10^5 CFU/ml, with the same strain as the previous infection (same strain, serotype, or antibiotic susceptibility profile), indicating recurrent infections. Urogenital superbug infections are associated with complex etiologies. These infections stem from multiple causes, including complex pathogens, predominantly affecting the entire urinary tract, involving deep infection sites that are challenging to clear, recurrent episodes, prolonged disease duration, and generally low patient immunity, rendering clinical treatment difficult.

2. Bacteriophage Therapy for Urogenital Infections

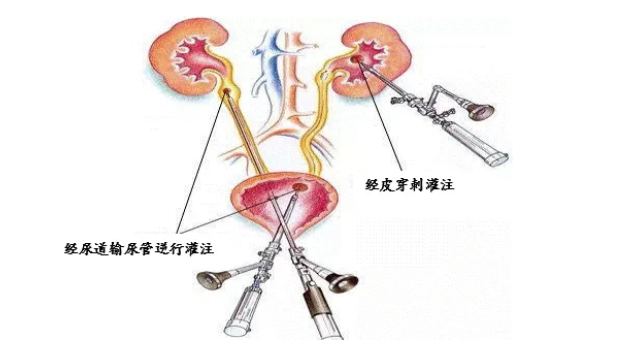

Currently, bacteriophage therapy for urogenital tract infections employs localized administration, achieved through three routes (Fig. 1): 1) transurethral bladder instillation for bladder and prostate infections; 2) transurethral-pelvic retrograde instillation for total urinary tract infections; and 3) percutaneous nephrostomy instillation for total urinary tract infections. These methods have developed into well-established clinical operational standards.

Fig. 1 Mode of Administration of Urogenital Bacteriophage Therapy

3. Key Points in Clinical Treatment of Bacteriophages

3.1 Pinpointing “Superbugs”

In clinical practice, it is essential to collect multiple urine samples to determine whether the acquired bacteria represent random infections or patient colonization, to analyze the presence of multiple infections, and to recognize that the urinary system—comprising the left and right kidneys, bladder, and urethra—may harbor different bacterial infections in various regions. Multiple samplings enable the identification of bacteria from different infection sites, facilitating the development of highly adaptable bacteriophages. During bacterial culturing, multiple isolations and selections of monoclonal colonies enhance the ability to target and capture specific bacteria. Our standards are accuracy and comprehensiveness. For patients exhibiting severe psychiatric symptoms or depression, the treatment process is susceptible to doctor-patient conflicts; how can we better manage such patients? Our approach is to exclude patients from clinical enrollment if no pathogenic bacteria are cultured, regardless of the severity of their clinical complaints; we accept enrollment if pathogenic bacteria are cultured and a lytic bacteriophage is identified. Through our treatment, eliminating pathogenic bacteria benefits the management of patients with mental health conditions.

3.2 Screening for Lytic Bacteriophages

Screening for lytic bacteriophages, the bacteriophages in our library’s repository, has undergone whole-genome sequencing to exclude resistant and harmful genes. The principle of bacteriophage screening involves evaluating, under various conditions, the bactericidal curves of bacteriophages to select strains with superior lysis effects and low tolerance, while considering phage morphology to assess stability, thereby creating a preferred bacteriophage cocktail.

3.3 Delivery of Bacteriophages to Infected Sites

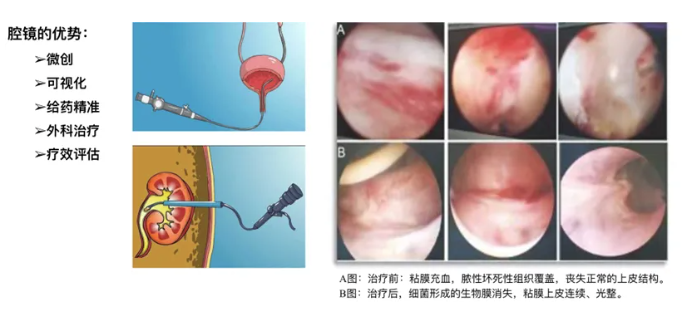

Another critical aspect of bacteriophage therapy is ensuring the delivery of bacteriophages to the patient’s infected site to achieve comprehensive coverage of the infection. Urological endoscopic techniques play a vital role, offering the advantages of minimal invasiveness, visualization, and the ability to observe conditions within the patient’s urogenital tract for precise catheterization and drug delivery (Fig. 2). We also integrated endoscopic surgical interventions to address the infectious etiology in patients, using laparoscopy to observe changes in urogenital epithelial tissue before and after treatment to assess therapeutic efficacy.

Fig. 2 Application of Endoscopy in Bacteriophage Therapy

In 2021, we admitted a patient with a long history of diabetes, bedridden due to a patellar fracture. Since May 2021, the patient has experienced recurrent fever, frequent urination, painful urination, dysuria, urinary retention, and residual urine volumes exceeding 200 ml. Urine bacterial culture revealed a multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. After more than two months of antibacterial treatment at an external hospital, the patient’s body temperature remained elevated, prompting a request for bacteriophage therapy and transfer to our hospital. Upon admission, a CT scan of the urinary tract identified a large cast stone in the right kidney, and we assessed this patient for urinary tract infection complications. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is the preferred urological treatment for multiple kidney stones and cast stones; however, it is contraindicated during periods of severe infection. We devised a treatment protocol combining bacteriophage therapy and surgical intervention; after two rounds of bacteriophage treatment, the patient’s body temperature was controlled, and the quantity of bacteria in the urine significantly decreased. We performed percutaneous nephrolithotomy with the aid of negative pressure suction equipment; pre- and post-treatment imaging examinations showed more thorough clearance of renal calculi. After more than a year of follow-up, the patient’s body temperature remained normal, urinary system symptoms improved markedly, the bacterial load in the urine decreased significantly, and there was no need for ongoing antibiotic maintenance therapy. Therefore, we conclude that bacteriophage therapy offers clear benefits for such patients.

4. Endpoints of Bacteriophage Therapy

Two endpoints were established in our clinical trial: 1) the primary endpoint: complete clearance of the target pathogen. That is, two consecutive secondary bacterial cultures were negative following bacteriophage therapy. 2) Secondary endpoints: significant improvement in clinical symptoms, including: I. Discharge or transfer from the ICU due to improvement; II. Improvement in urinary system symptoms, such as normalization of body temperature, normalization of urine, and marked alleviation of urinary pain and low back pain (for upper urinary tract infections); and significant lesion improvement observed via laparoscopy and imaging examinations.

Conclusion

Bacteriophage antibacterial therapy still faces numerous challenges requiring further study; we hope it can be integrated into clinical practice as soon as possible, benefiting the majority of infected patients.

That concludes today’s discussion. If you find this article valuable, feel free to follow, like, watch, or share it with friends, or explore more about kidney transplantation. Until next time.